Press & Contact

Catherine Rodgers Contemporary Art

Tanglewood Center, Suite 113

7509 Cantrell Road

Little Rock, AR 72207

501 690-3819

catherine@catherinerodgers.com

Represented by:

M2 Gallery

1300 Main Street

Little Rock, AR 72202

501 225-6256

m2gallery@hotmail.comitemscope

Catherine Rodgers loves color. And resin. And Plexiglas. Born and raised in Little Rock, she has been a full-time artist for over twenty years striving to create unexpected, high-quality artworks that bring joy and wonder to each observer.

She credits the veil paintings of Morris Louis and the color field paintings of Mark Rothko for much of her inspiration. Pushing a paint brush around to create portraits was part of her early training and work but she prefers to let colorants and resin seek their own expression. Examples of her techniques can be found in the Cascade Series, the Deconstruction Series and in her round Plexiglas installations.

Experimenting with new mediums and problem solving are what bring her back to the studio virtually seven days a week. She understands how color effects the human psyche and her collectors often describe her work as happy and energetic.

Catherine’s artworks are held in hundreds of private and corporate collections nationwide. She teaches internationally and has served as faculty at the Arkansas Arts Center since 2012 (now known as the Windgate Art School at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts). Additionally, she teaches small groups and private classes at her studio, Catherine Rodgers Contemporary Art and her artworks have been shown in numerous exhibitions including the 55th Annual Delta Exhibition.

Arkansas Democrat Gazette

Five questions with artist Catherine Rodgers

by Philip Martin | March 13, 2023 at 1:50 p.m.

Little Rock artist Catherine Rodgers with some of her work. (Photo courtesy Catherine Rodgers).

Catherine Rodgers loves color. And resin. And Plexiglas.

Born and raised in Little Rock, she’s been a full-time artist for more than 20 years, and her works are in hundreds of private and corporate collections nationwide. She teaches internationally and has served as faculty at the Arkansas Arts Center since 2012 (now known as the Windgate Art School at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, scheduled to reopen after major renovations in the spring).

Additionally, Rodgers teaches small groups and private classes at her studio Catherine Rodgers Contemporary Art, and her works have been shown in numerous exhibitions including the 55th Annual Delta Exhibition.

Rodgers credits the veil paintings of Morris Louis and the color field paintings of Mark Rothko for much of her inspiration. While she began her artistic career as a portraitist, these days she “prefers to let colorants and resin seek their own expression.”

Examples of her techniques can be found in the Spatial Series, the Urban Series, the Cascade Series, the Deconstruction Series and in wall sculptures and round Plexiglas installations.

Q. How would you describe your work, and how did you come to it? Has making art always been part of your life, or is there a conscious moment when you decided to become – or that you were – an artist? And is there a spiritual as well as intellectual component to your work? How has it evolved over the years?

My artworks are happy. That seems simplistic, but it is the common thread that runs through my eclectic body of work. I remember reading an interview with Lucien Freud and he was asked, “What is the hardest thing about being an artist?” He answered, “being the same every day.” I share this because I never know what I am going to create when I arrive at my studio each morning.

I love color and working with a variety of materials such as resin, Plexiglas, wood, wax, wire, plaster, clay, concrete and a variety of colorants. The tactile experience of working with various materials is very satisfying and I come by it naturally. My father and both grandfathers were perfectionists in their professional careers. They worked long hours in the building trade and took great pride in their craftsmanship. Credit belongs to them for my work ethic and love of creating art.

My maternal grandfather was a plasterer. While visiting the Little Rock Zoo as a child, my mother shared stories of how he built the large outdoor sculpture based on the nursery rhyme “There Was an Old Woman Who Lived in A Shoe,” and he also played a part in building the oversized sculpture of the Orange Pumpkin. Those two sculptures greeted visitors to the zoo for many years. Using simple materials of wood, wire and plaster, my grandfather created birdbaths, outdoor furniture and plant stands in his spare time. My collection of plaster wall sculptures is my homage to him.

Making art has always been a part of my life. I remember painting murals on my bedroom walls when I was very young, and luckily my parents didn’t seem to mind too much. During the summer months, they took me to the Arkansas Arts Center for painting and acting classes. I vividly recall playing the part of a tree swaying in the wind in a summer play when I was maybe 7 or 8 years old. It’s their fault that I am a tree hugger.

I have been a full-time artist for over 20 years, but the path to get to this point has not been a straight one. Before committing to art, I received an MBA and worked in the voice and data industry selling systems and software to banks, hospitals, and other large corporations. I traveled the country constantly.

One day, flying home from the east coast with my boss, I realized I was missing another one of my son’s football games. At that moment, I told him I would stay long enough to close the two deals I was working on and then I would resign, which is what I did.

After that, I sat at the top of Pinnacle Mountain and thought about what I would do next in my life. I loved the practice of yoga and decided I wanted to bring more of it to Little Rock. I traveled to study yoga and returned to open Barefoot Studio, which I owned and operated for seven years.

I share this history because these two work experiences have played a major part in my success as an artist. Understanding the business of marketing a product and the focus that comes from the practice of yoga have been invaluable. I consider the creation of art to be a meditation. When I am working at the easel, time slows, and it is truly living in the moment with total focus.

Q. Unlike a lot of artists, you seem to recognize the need for promotion and marketing and happen to be very good at it. Can you explain both your philosophy about selling art and the need to promulgate an artistic brand? What advice do you have for artists and would-be artists?

The four Ps of marketing were branded in my brain when I was in graduate school: product, place, price, and people. There is rarely a week that goes by when a fellow artist doesn’t ask me to evaluate their work and give advice on how to sell more. It truly is as simple as understanding the four Ps. Who is your customer? What do they want to buy? How will you distribute your artwork? How much will your customer pay for your art?

In addition to identifying the four Ps, the advice I most often give to fellow artists is simple: Clearly identify the name, medium, and price of your artwork, prepare the artwork for hanging, display the artwork with space around it to breathe, maintain a mailing or email list, and if you are presenting your work at an art fair, don’t sit down. It’s important to stand and greet your prospective collector and engage in conversation.

In the case of my work, I try to create something new and unexpected, something that has never been seen before. Sometimes the work is successful and sometimes it is not. Either way doesn’t really matter. It’s the process of creating and problem-solving that keeps me in the studio. Some artists find a style that works for them, and they continue to create that style over and over. I would be bored working that way. It’s the exploration that I find exciting.

Little Rock artist Catherine Rodgers with some of her work. (Photo courtesy Catherine Rodgers).

Q. How has your work evolved over the years? You seem willing and eager to embrace new materials and techniques.

Many of my earliest paintings were portraits. It may sound counterintuitive, but painting a portrait is easier than painting an abstract. With portraits, you paint what you see, but first, you must learn how to see. Line, perspective, color, shape, value, form, and other elements of art form the foundation. These same elements are necessary for a successful abstract painting without portraying something that physically exists like the landscape, still life or portrait.

The transition from painting something that is representational to painting abstracts took years for me to achieve. While preparing for an Abstract Expressionist painting class that I will be teaching for the Arkansas Museum of Fine Art later this summer, I realized how grateful I am to the New York School. There is a freedom in this intuitive art movement.

While their artistic styles differ, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, and many others led the way to the use of color, gesture, and non-representation in art.

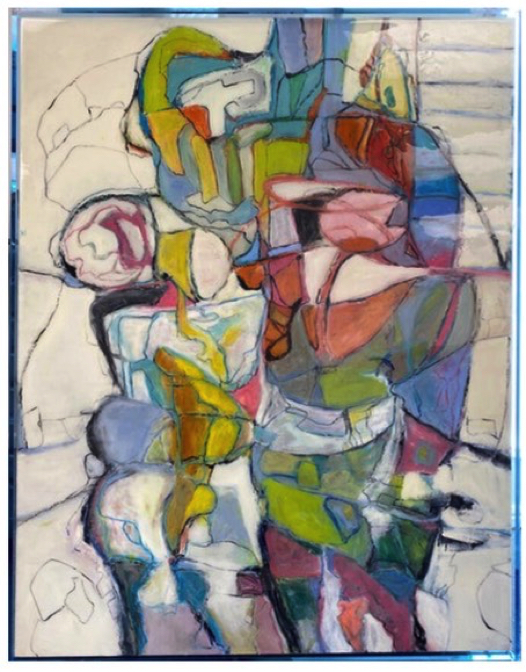

The Urban Series is one of my abstract offerings. About 17 years ago when Google maps was introduced, I used the aerial view maps as a starting point for painting abstract landscapes. As a child, I flew a lot in my dreams, making this viewpoint of looking down to the Earth from the sky familiar. The Urban Series has grown over the years, but it still is my representation of a landscape.

I enjoy using a variety of materials and techniques. Artists often attempt to create the illusion of three dimensions in their two-dimensional paintings. My newest body of work, The Spatial Series, is an attempt to give depth to paintings. It consists of three layers of painted acrylic sheets encased in a four-inch-deep clear acrylic box.

While I don’t know for sure what the next body of work will be, I am confident there will be one. I wake up in the morning with new ideas swirling in my head and can’t wait to get to the studio and work. I am all about moving forward, but when requested, I will do consignments that relate to previous works. Lately, I’ve been thinking a lot about wood. I can visualize new wall artworks made of painted wood cobbled together. We’ll see.

Q. Do you have favorite tools or require a particular space to do your work? How important is the right studio space? And is routine important to your process or can you wait for inspiration?

I have three workspaces. I rent a studio space in Tanglewood Center on Cantrell Road in Little Rock. It’s where I go every day to work. I have an air filter system that is essential when working with resins, and the large windows provide beautiful natural light. This is where I work when I need a very clean environment, and it’s a space where I can meet with clients about consignment projects.

I also have a 4,200-square-foot woodworking shop. This is where we make frames, pour paint on large canvases, and construct other art objects.

The third workspace is my home office where I maintain my website and take care of correspondence.

Back in my yoga days, we would share how important it was to “just show up to your mat.” Even if you didn’t feel like doing a practice, go sit on your yoga mat and eventually you would get up and start practicing. It’s the same for me when creating art. I have developed a habit of going to the studio virtually every morning. I turn on great music and the inspiration just takes over.

Q. How can someone see your work? In addition to private collectors, I understand you have several large commercial installations. Would you name a few?

My artworks can be seen at Catherine Rodgers Contemporary Art in Tanglewood Center and at M2 Gallery in Little Rock’s SOMA District. My website is catherinerodgers.com, which lists many of my artworks and where they are currently located.

Last year we installed five or more major artworks at several business locations in central Arkansas. They include the corporate offices of the Arkansas Federal Credit Union in west Little Rock, Clark Orthodontics in North Little Rock and the Country Club of Little Rock.

Little Rock artist Catherine Rodgers with some of her work. (Photo courtesy Catherine Rodgers).

Arkansas Arts Scene Interview

by Philip Mayeaux

AUG 10, 2020

Interview with artist Catherine Rodgers

Catherine Rodgers is all about creating – and that comes through in the breadth of her work and what she describes as her eclectic style. She is fearless in the studio. A native of Arkansas, Catherine has deep family ties to Little Rock. In addition to being a full time artist, she is an art writer and art instructor and she manages her own gallery, Catherine Rodgers Contemporary Art in Little Rock. Her textural mosaic-like abstracts can be found there and at her website.

Urban 12, acrylic, oil, pastels and colored pencil on canvas, 48” x 60”, from the ‘Speed Painting Project’

AAS: You’ve said you always loved art and always wanted to paint, but you have other interests as well. Talk about that.

CR: My father and both my grandfathers were perfectionists in their professional careers. They worked long hard hours in the building trade and took enormous pride in their craftsmanship. Credit belongs to them for my work ethic and love of creating art.

Working with a variety of materials is what I find interesting. Painting teaches the basics such as color theory, form, light, shade, line, and perspective, but there’s so much more. It’s a satisfying tactile experience to work with plaster, plastic and concrete, but problem-solving, an integral part of the art process, is the most satisfying. That’s what keeps me in the studio virtually every day.

Catherine in her studio.

AAS: How has your education in business administration helped you become a gallery owner and full-time artist?

CR: Before becoming a full-time artist I worked for major corporations in marketing, and I am the founder of Barefoot Yoga Studio, so I am comfortable with the sales process and owning my own business. The marketing of art is different from other types of retail and has an interesting past.

In the mid-19th century, French art dealer Paul Durand-Reul supported artists with stipends and solo exhibitions. He is considered the first modern art dealer and played a significant role in the acceptance of the Impressionists. In the past, dealers purchased the entire collection of paintings from an artist and resold them for a profit.

Today, most galleries are consignment shops. The artist delivers his or her work to the gallery and receives nothing unless it sells. Commissions can be up to 50 percent of the sales price, and the artist has to agree not to sell his work below the gallery price and/or within a certain region of the country. Basically, the artist gives up control of his product and is at the mercy of the art dealer to promote and sell the work.

Galleries have represented me in the past, and part of me would like to be represented by one again because I would like for more people to see my work, but they would have to promote my work with more enthusiasm than I can represent myself. With the abundance of social media, it’s easy to have your work in front of potential collectors. Holding sales at my art studio and having a personal relationship with my collectors are benefits of representing myself. This doesn’t happen when works are sold through galleries. I do, however, offer the same services as galleries, including delivery and installation of artwork in central Arkansas at no charge. Another advantage of selling my own work is that it is more affordable than what one would expect to pay in a gallery.

“My teachers helped me get to where I am today, so teaching is my way of paying it forward.”

AAS:: You do a lot of commission work. How did you become known for that?

CR: I think it all goes back to the Arkansas Arts Center. Over the years, and whenever my schedule allowed, I enrolled in classes: furniture, jewelry, painting, watercolor, and pottery. My home collection of art was becoming overwhelming so in an effort to free up space for more art, I reluctantly signed up to participate in the Arkansas Arts Center Museum School Sale. No one was more surprised than me when I sold out quickly and was number two in overall sales. Jim Johnson, of Cranford Johnson Robinson Woods advertising agency, was well known at that time for his position as the top seller. Being a twin, and thus naturally competitive, my sights were set on being number one. For the next 6 years, if my memory serves, I was the top seller. I don’t know to this day if Jim knows I had my sights set on him. It was my silent little competition, and it made me a better artist. I am grateful to Jim. That’s where it all started. Galleries were reaching out to represent me and collectors started requesting commissions. Artists ask me often how I sell so much work and get so many commissions. I really don’t know how to answer that question. I work hard, I love what I do and I’m not attached to the outcome. I create work that makes me happy and gratefully, it makes others happy, too.

AAS: You are also a journalist. How did you get started writing about art?

CR: I’ve written about a variety of subjects that have interested me over the years. In the mid-80’s and during the divestiture of AT&T, I wrote telecommunications-related articles for Arkansas Business. After I sold Barefoot Studio in 2002, I was asked to write spa and health-related feature articles for the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette, which led to writing their Personal Space column for eight years.

Today, my interests are all about art. My husband and I enjoy traveling and we have attended Art Miami Week and Art Basel several times. Writing about art is just a natural progression. Seeing what’s new in the art world is thrilling and something we look forward to each year.

Rural Route, colorants, trash, acrylic and resin, 42” x 62”

AAS: Teaching art seems to be something you really enjoy and do a lot of.

CR: My teachers helped me get to where I am today, so teaching is my way of paying it forward. It all started with the Arkansas Arts Center. It’s a gem, and has been a part of my life since early childhood. I recall playing the part of a tree swaying in the wind in a summer play when I was maybe 7 or 8 years old. It's their fault that I am a tree-hugger and I have painted this image.

Several years ago, the Arkansas Arts Center asked me to become a member of their faculty. I teach workshops when my schedule allows. At this stage of my life, my interests are focused on creating art and the majority of my work is commissioned. It’s difficult to commit to a long-term teaching schedule, but I enjoy teaching weekend workshops. I also teach annually at Rancho La Puerta Resort and Spa in Tecate, Mexico.

AAS: You work a lot with Plexiglass [acrylic sheets] and resin. What is it about that medium that interests you?

CR: Technology makes it all possible. With CNC routers and lasers, you can create any shape you can think of out of acrylic sheets. They are available in a beautiful array of colors and choice of fluorescent, transparent or opaque. Add resin on top of the acrylic and the possibilities are endless. Resin is an amazing medium that is glass-like in appearance, but much more durable. Almost any colorant can be added to resin to be used in a painting, a mold, or simply poured over a canvas, wood, or acrylic. I am self-taught when it comes to resin, so I was never told that I couldn’t do something with it. If I can think of a project, I have tried it. Sometimes they fail and sometimes they are successful, but I love them all.

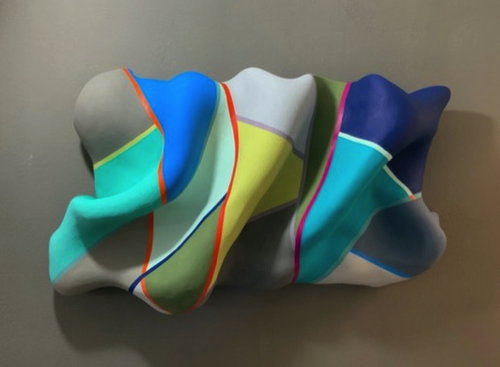

AAS: Some of your acrylic wall sculptures remind me of the colorful millefiori glass canes used to make paper weights, but, of course, on a much larger scale.

CR: Observers have also told me they look like buttons, but in reality, most of the pieces are 6 inches in diameter, so much larger than millefiori. Rural Route is over 5 feet wide, and A Dozen Butterflies is also large. They are both made of poured resin and colorants and designed to look like flowers. However, the process is somewhat different for these two artworks. Hundreds of pieces designed to look like flowers were created for Rural Route. Some of them even have small pieces of trash embedded in them. They are individually attached to an acrylic substrate using varying lengths of acrylic rods to give the artwork depth. A Dozen Butterflies consists of numerous layers of resin and colorants poured on top of a clear acrylic five-sided box with a French cleat attached for hanging. It gives it a 3-D appearance and the image seems to float off the wall.

6. AAS: One of my favorite pieces is Totem. I see something new every time I look at it! Does it incorporate resin to give it added depth?

Totem, resin, pigment on canvas, 50” x 62”, framed in blue acrylic

CR: Totem is comprised of several layers of poured resin combined with colorants over canvas. It’s framed in fluorescent blue acrylic, which is my favorite framing material. The process starts by combining resin with hardener and mixing by hand for several minutes until the mixture becomes clear. At that point, you have 45 minutes to use the resin before it starts to heat up and cure. Next, a small amount of resin is mixed with the desired colorant and poured on a canvas to create the painting. Almost any colorant can be added including oil paint, acrylic paint, alcohol inks, and powdered pigment. It’s best to let the painting cure for 24 hours before adding a second layer of resin. I don’t recall how many layers of resin are in Totem, but it is about 8. After I am happy with the image, I add another layer of clear resin on top to give paintings a smooth finished look.

I have always loved totems because of their spiritual significance. They often display reverence for animals and plants and identify one’s clan or tribe. My heritage is Scottish, English, Irish and American Indian, thus, an indescribable totem.

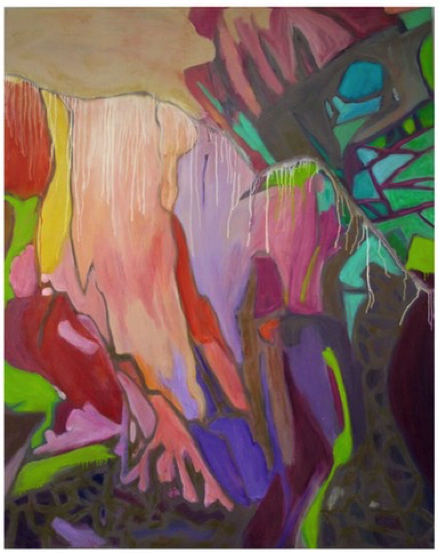

Quietly Whispers, pigment, hot wax, cold wax on canvas, 60” x 48”

AAS: Your wax paintings also have an added depth and texture. Talk about that process.

CR: I am drawn to working with wax because of its permanence and historical background, plus the brilliance of color and visual effect. The wax process is simple. Pigment is mixed with beeswax and resin and worked from a warm palette, using a brush for hot wax applications. The final treatment is use of a heat gun to fuse and bond the painting. For cold wax, a solvent is added to the wax and pigment mixture, softening it for application with a palette knife. One advantage in working this way over oil paint is the painting hardens quickly compared to slow-drying oils. An added benefit is that my studio smells like honey when I am working with beeswax, making it a delightful experience. Bees have even dropped by, as if they have found their home.

Symbols, plaster, wire, wood and paint, 30” x 40”

AAS: I love your wall sculptures, especially Symbols. What inspired you to start working with that form?

CR: It’s paying homage to my maternal grandfather, who was a plasterer. Using simple materials of wood, wire and plaster, my grandfather created birdbaths, outdoor furniture and plant stands in his spare time. Local residents may remember some of his work. As a child, my mother shared stories of how he built the large sculpture There was an Old Woman Who Lived In a Shoe, based on the nursery rhyme, and the enormous Orange Pumpkin at the Little Rock Zoo, which greeted visitors to the zoo for many years.

Curvaceous Lines, plaster, wire, wood and paint, 30” x 40”

AAS: Talk about your recent ‘Speed Painting Project’.

CR: The pandemic we are in the middle of is horrific on so many levels. I simply wanted to make art more available and affordable to everyone who is spending significant time in their homes. Using acrylic paint and only allowing myself a few hours to complete the works (in most cases), the Urban series [in the first collection of works above] is a group of abstract paintings priced at one-half my normal price for a painting. I am revisiting a series of images I painted years ago that are landscapes viewed from the sky. As a child, I flew in my dreams, and these are memories from that time.

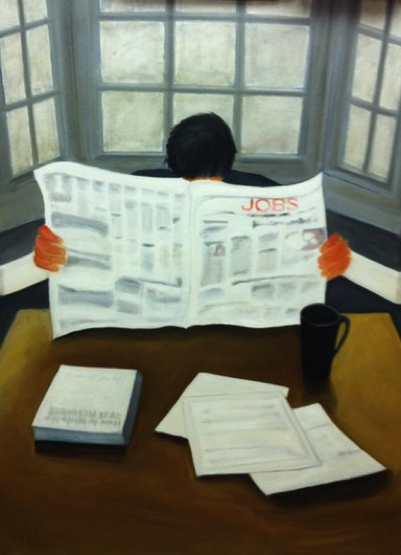

Jobs, oil on canvas, 48” x 36”

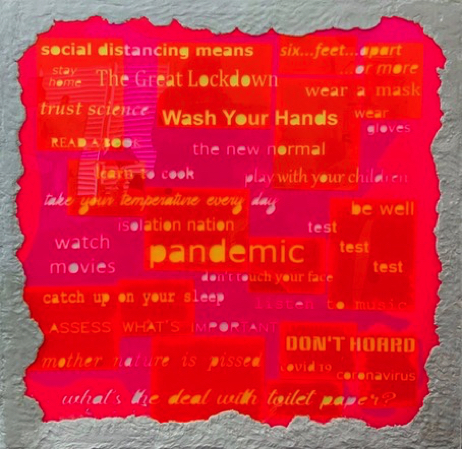

AAS: Your works Jobs and Pandemic were created to document significant events of the time. Would you comment more on the importance of doing that?

CR: From the time of cavemen, artists have been recording history. Picasso’s Guernica, a famous anti-war painting, is another example. Most of my collectors describe my work as happy and joyous. Bringing beauty into the world is what I strive to do, but sometimes current events call me to the side. I painted Jobs shortly after the financial crisis of 2008. Pandemic [see below] is my current offering to history. It is a constructed of bright fluorescent pink and yellow acrylic that almost shouts at the viewer. Words and saying associated with Covid-19 are laser cut into the acrylic to memorialize this time and the frame is made of concrete to symbolize the weight upon humanity. Life is a balance. As artists, we need to keep our eyes open and see all of it.

AAS: In Pandemic, you write, “assess what’s important”. What has kept you going and sane these last months?

Pandemic, fluorescent acrylic, resin on canvas, 50” x 50”, framed in lightweight concrete

CR: Being an artist is like being cloistered. I have worked alone in my studio for 16 years, so honestly, it’s not that different. I do miss having coffee and lunch with my friends, but gratefully, art collectors are still requesting commissioned work. I just started an eight-foot-wide resin arch that will span an entryway for one collector, which will keep me busy for a while. When I am not working on a commission, I have a chance to explore new work, and there are many ideas swirling in my head. That’s the best thing about being an artist: you are never bored.